In an unjust society like India, two questions are often asked. Why don’t the poor and the oppressed rise up to demand justice? And how do the powerful and the exploiters continue to stay in power despite the glaringly obvious injustice all around them?

There are three usual sets of answers to these questions. The first blames the oppressed themselves. People are too ignorant, too divided, too blinded by caste and religion, or too selfish to do anything. The problem with this is that it simply isn’t true that people don’t fight. There is no part of India where there is not some kind of protest or agitation underway. The mystery is not that people do not fight; it is rather that their struggles do not go further.

The second set of answers then revolves around the strength of the ruling class. Most simply, some point out that the rulers have force at their command – they have the courts, mafias, the army, the police and other instruments, and these are routinely used to crush the struggles of those fighting against them. However, this only begs the question further. In the face of a united struggle, these tools cannot win; they cannot kill everyone. Moreover, those who are part of these forces themselves mostly come from working and poor backgrounds. Why do they obey?

The second set of answers then revolves around the strength of the ruling class. Most simply, some point out that the rulers have force at their command – they have the courts, mafias, the army, the police and other instruments, and these are routinely used to crush the struggles of those fighting against them. However, this only begs the question further. In the face of a united struggle, these tools cannot win; they cannot kill everyone. Moreover, those who are part of these forces themselves mostly come from working and poor backgrounds. Why do they obey?

This brings us to the third set of answers, which are responses to the question – why don’t we see a larger and more united struggle? It has often been pointed out that the ruling class divides people, that it prevents them from seeing their oppression and their common interest, and that it manages to create a situation where people accept their oppression and do not see the possibility of rebelling.

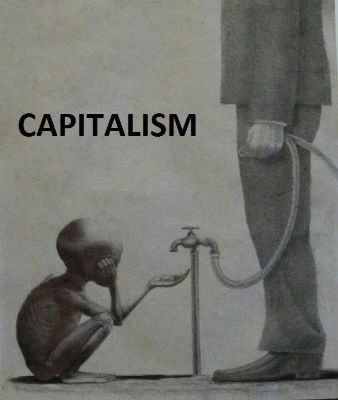

The Impossible Objectives of a Capitalist Ruling Class

In this context, it is important to understand what a capitalist ruling class seeks to do. Obviously, every ruling class seeks to maintain its own power and its ability to exploit the rest of society. But a capitalist ruling class has specific problems that it has to address. These can basically be broken down into three categories:

- They need workers and producers who will engage in production and accept their exploitation without resistance, or with resistance kept at a minimum level. Obviously, without human labour, nothing can be produced and no profits made.

- They need these workers and producers to reproduce themselves, so that production can go on, and they need a market to sell their goods. Both of these require that there should be enough money in circulation (through wages, through loans, etc.), and moreover being used in an appropriate manner, that the capitalists can carry on producing goods in a reasonably stable way and also earn the profits they wish to earn.

- They need to ensure that the competition between individual capitalists and each capitalist’s attempts to get more profits are within reasonable limits. For instance, if companies frequently physically attack their competitors, the resulting violence will destroy everyone’s profits. In other words, capitalists need sufficient “social harmony”, both between capitalists themselves and between capitalists and producers, or the system will disintegrate into chaos and mutual robbery.

- At every stage, the exploiters try to keep a step ahead of the oppressed by preventing them from becoming organised. Therefore, the first step is to struggle in a manner that helps to the oppressed. In this view organising is not a step towards some other goal – for instance, higher wages, better welfare, revolution, etc. – but is itself the goal. Demands for concrete gains are essential, of course, but they should be understood as a means for organising people.

- The power of capital ultimately stems from its power over the production process. Hence, at every stage, threatening this control is an essential part of the struggle for power and opportunities should be sought for doing so.

- As noted above, every idea in the existing system is a hybrid. Rather than rejecting them, the focus is on demonstrating how they are internally contradictory – and hence how the ruling class is lying. Through such actions, struggles can also disorganise the ruling class. The key purpose is to expand contradictions within ruling class ideas and thereby put them in a position where they must either expose the system as a lie or concede the demand.

The key to understanding the current political system is to realise that it is actually impossible to achieve any of these objectives in any permanent or complete manner. The first objective is impossible because, as noted above, people can and do resist their exploitation, and they always will. Whatever methods the rulers come up with suppressing this resistance in turn leads to new forms of resistance. The ruling class cannot indefinitely predict what kind of resistance will emerge, how far it will spread and how effective it will be. They may succeed 99% of the time, but they have no guarantee that they will always be able to do so, and history is replete with examples where the ruling classes of particular countries failed to do so.

The second objective is impossible because the inherent tendency of individual capitalists is precisely to try to suck as much profit as they can out of the system. Periodically, this leads the entire system into a crisis. When the capitalists get too strong and overexploit their workers, they find that society does not have enough money to pay for their goods, and their profits collapse. This kind of “crisis of overproduction” is a recurrent feature of capitalism since it originated centuries ago. It is a key cause behind the current (2008 onwards) crisis in the world economy. Moreover, in order for the working class to survive and develop the skills required for greater production, a state machinery that provides health, education and other basic requirements is needed, as well as the basics of public safety and security. However, capitalists themselves often seek to destroy such provision in order to increase their profits and decrease their costs (that is, their taxes). This self-destructive behaviour in turn leads to crisis. In short, the system is the victim of a paradox – it seeks to protect the power and profits of the exploiters, but every time their power increases too much, they cut the ground from under themselves.

The third objective is impossible because, just as with the resistance of workers, there is no way to predict how individual capitalists will seek new ways to out-compete their rivals – and they never do so purely through the “good” means of out-selling them in the market. A good indicator of this is the fact that every country in the world periodically faces corruption scandals, accusations of monopolistic behaviour by large companies, or financial collapses due to illegal behaviour by corporates and banks. As a social system, capitalism is a chaotic mess that at best can be a controlled anarchy.

In sum, what we see around us is not the result of a ruling class that is completely in control. Rather, what we see is an unstable, dynamic and constantly changing political scenario where the rulers are themselves continuously racing to keep up with events.

This is also the reason for the vast diversity of types of states in the world today, even though it is clear that they all function under capitalism. These include functioning parliamentary democracies, half-functioning democracies, absolute monarchies, constitutional monarchies, military dictatorships, one party systems, governments in transition between these types, and ones that don’t fall fully into any of these categories (such as the Iranian regime). Since no solution to the problems of a capitalist ruling class can be either complete or stable, there is constant change and variety.

Hegemony

The overall result of this continuously unstable process, until revolution, is what Antonio Gramsci referred to as “hegemony.” Those who are oppressed, the producers and workers, resist and fight for greater control and a greater sense of dignity. The ruling class can never take either their consent or their exploitability for granted. In turn, sections of the exploiters attempt to concede certain matters – most obviously in the form of various “benefits”, but in a more complex fashion through respecting political freedom, attempts to coopt or confuse the issue, etc. – in order to deflect, disorganise or minimise resistance. Various “experiments” are tried. Where these other methods fail, the rulers can always turn to repression as the last resort, but this is usually combined with other efforts at the same time.

The net result of these processes is that the exploiters are forced to grant certain real freedoms, benefits and forms of respect. It is important to reiterate that, in addition to whatever fake things the rulers offer, the fundamental benefits are in fact real material gains. But the basic feature of this process is that these real benefits are not seen as a victory of working class resistance. Instead, there are two ways in which these benefits are talked about. The first is the idea of the “general good.” Welfare benefits are given, political freedom is respected within limits, and some measure of security offered, but all in the name of the fact that these things are “good for everyone.” Words like “development”, “welfare”, “helping the poor”, “national interest”, etc. all express the basic idea that the system works for “everyone.”

The second key claim is that “everyone” consists of a group of individuals – “citizens” – who are all equal “before the law” and who are provided different things in order to ensure that “everyone will progress.” The “system” supposedly relates to people as individuals, and whatever it provides them, it does so as a result of their “rights.” Even where benefits are based on group identity – such as caste-based reservations – they are given to the individual based on him/her belonging to a wider caste – not as an explicit acknowledgment of the class or caste struggle that led to these victories. It is because the person is a “citizen” that they are given their “rights” – not because they are part of a class or caste or other collective that has fought for them.

It is important to note that this entire process of mutual struggle, victories, deflections, and so on is always underway. It is not only applicable to revolutionary situations or when there is an uprising by the oppressed. Indeed, if one can see past the words that are used, one can see evidence of this struggle all around. It is first important to note that exploiters do not only fear consciously-organised revolution. They also fear three other things: first, “disorder”, “anarchy”, “crime”, “insecurity”, etc., all of which are words for disorganised or non-conscious resistance (and at times are applied to conscious resistance too). Second, they fear intra-capitalist contradictions becoming too severe. Finally, they fear poverty and destitution intensifying too much, since that threatens their ability to produce and also breaks the illusion of a state working for the welfare of everyone.

With this in mind, one has only to glance at the pages of any English newspaper in India to see the constant debates about how to respond to these threats. The debates talk of the need to stop “corruption” (i.e. inter-capitalist rivalry), the need to deal with “crime” (i.e. reduce violence and resistance), to ensure ‘fast growth and development’ (i.e. to increase production and/or profits), to ensure that the “economy” is “better managed” (i.e. that production happens more smoothly), to get “welfare schemes” more operational (i.e. to ensure that the claim of working for all is not belied), etc. As for resistance, one has to only look out of the window in any major Indian city to see resistance, disorder, conflict and anger among workers and producers.

The ruling and exploiting classes enjoy four advantages in this struggle. First, as a fundamental feature of capitalism, they have a longer “time horizon” – they do not need to worry about starvation or joblessness, and hence can plan for the future. Second, they are better organised, as discussed below. Third, as a result of both of these features, they have a sense of their common interests and identity that is far stronger than that among the working classes. Fourth, they have access to and command over considerably greater physical force than the working and producing classes.

It is important to note that all of the ruling class’ advantages are relative advantages, not absolute ones. The fact that the exploiters can set their agendas with a longer time horizon does not mean they can anticipate or plan for everything that will happen – in fact, they routinely fail to do so. Their internal organisation and their sense of common interest, as noted above, are constantly threatened by their own internal contradictions. Their command over physical force is not absolute and itself may be threatened at a time of crisis – witness the fact that every successful revolution has seen large parts of the army and the police joining the revolutionaries.

In short, the ruling class does not sit outside the system and drive it. Rather, the defining feature of politics in a capitalist society is the fact that the actions of everyone, exploiter and exploited, are defined by the constantly underway and always unpredictable struggle of the oppressed against oppression.

The State in a Capitalist Society – Ideas and Institutions of Rule

It is the state that serves as the main and central mechanism for managing these conflicts and struggles in a capitalist society. This state itself has some peculiar features.

First, it is not clear where it begins and ends. It is obvious, for instance, that the police and army are part of the state. But are panchayats part of the state? Gram sabhas? Political parties? Indeed, there are volumes of court judgments in India that try to define what is and is not the state for legal purposes. Recently there has been controversy about whether political parties are state authorities or not and hence whether they should be subject to the Right to Information Act.

Indeed, the closer one looks at the state, the more confusing it becomes. Different institutions repeatedly clashed. For instance the courts overrule Parliament, or vice versa. In neighboring countries, the army overthrows elected governments. State governments resist the Central government and vice versa. Sometimes the police go on strike or soldiers turn on their commanders. Moreover, one cannot say that these clashes are temporary incidents which end with stability. On the contrary, clashes and tensions are practically continuous. Which of these institutions represents the “state”?

The reality is that there is no clarity on what the state is because the state does not exist as a single separate entity. What we call the “state” is a collection of different but closely related institutions that function in various ways. They have certain limits that they will not cross – for instance, no state institution will advocate the abolition of private property – but within those limits there is great space for conflict and different interests. Indeed, the very idea of a single, rational, organised state is itself a myth. It is promoted as part of the sense of a benign, organised, omniscient ruling class that functions for “the general good.” Instead, the institutions of the state are themselves both battlegrounds where struggles for power are fought as well as parties to the struggle themselves.

Each state institution is marked by this struggle in different ways. The bureaucracy, the “government officials” that are everywhere in our lives, are supposed to implement the policies of the “elected government”; but in practice they never do this. The lower bureaucrats, the State and local officials, respond most to the local manifestations of the struggle – most of the time they follow the dictates of the powerful elements or agents of the ruling class, while also defending their own power in order to take a share of the surplus. Indeed, reflecting the contradictions within the ruling class, these lower bureaucrats are often the target of big capitalists’ ire (witness all the complaints by corporates and “professionals” against lower officials). These lower bureaucrats also in turn have to face and respond to popular resistance, and they try to constantly ensure that such struggle does not become a threat to their own power. The higher bureaucrats, especially the IAS officers at the Central and State levels, function as “think tanks” for the ruling class. It is the bureaucrats who draft, check and record laws; bureaucrats who issue the orders that put those laws into practice; bureaucrats who block, permit and encourage various political ideas; etc. Within this different sections of the bureaucracy take up the interests of different sections of the ruling class. Some, those in the so-called “welfare” departments, are charged with responding to resistance and struggle while ensuring that these do not go “out of hand.” Indeed, when we think of the “state”, most of the time it is this higher bureaucracy and “think tank” function which one actually has in mind.

The police, army and paramilitary forces act as the arms of repression, but they too have their internal tensions and contradictions, particularly the police. The difference between these institutions and the “civilian” bureaucracy is that their role in “welfare” is much smaller and their role in defending ruling class interests is more open. However, the big capitalists in particular expect these institutions to both crush and ‘manage’ conflict in order to prevent any threat to the existing order. In the long run this is of course impossible, but the Indian police and army regularly fail to achieve even in the short term.

The judiciary plays a similar role to the bureaucracy; on paper, it is supposed to ensure that “the law is followed.” In practice the lower courts function in a similar manner to the lower officials, balancing locally powerful interests within the limits of the overall system. The higher judiciary – particularly in the last three decades – is increasingly preoccupied with defending the interests of certain sections of the ruling class against others, while simultaneously trying to make the system seem “rational.” Over this period the higher judiciary has increasingly taken over the role of articulating the “national interest” and tries to project itself as doing so through its judgments. This is then contested both by various forms of popular resistance and by other sections of the ruling class.

Electoral Democracy

Then there is the system of elections, elected State and Central governments, and political parties. There are two common ways that this system is usually looked at. It is routine for people to say that all parties are the same; no one wants to do anything that will genuinely help the poor; many point out that most ‘real’ issues are simply left out of political debate. But on the other hand there are clearly also differences between parties, and the majority of adult Indians do participate in elections, implying that they see some meaning in them. Which of these two viewpoints is then the correct one?

The reality is that both are half-true. Because of the power of the capitalists themselves, as well as the bureaucracy, the army, the courts and other unelected institutions, any elected leader who directly attempts to threaten the power of capital directly will not be permitted to do so. On their own – without a popular struggle – elected leaders are, in this fundamental sense, indeed quite powerless. It is in this sense that our “democracy” is certainly a lie. It is true that no government or political party can truly represent the “will of the people” and end exploitation – not because they are all corrupt, but because that exploitation is rooted in capitalism.

However, once again, within this absolute limit, there is a lot of real difference, contest and conflict. To see this one has to recall, once again, that no full solution is possible to the problems that face a capitalist ruling class. Hence there is both endless internal debate and internecine warfare within the ruling class, as well as constant challenges to their power from outside. This is reflected in the political system. Different sections of the ruling class, or different schools of thought within it, prop up different parties that advocate their preferred solutions to these problems. Through popular struggle new parties emerge or existing parties are forced to change their policies to respond. None of this can be fully managed by anyone and hence there are periodic efforts to keep the confusion “under control.” The only reason that the ruling class is forced to accept such a limited democratic system is because the alternative – dictatorship, military rule, etc. – is, in the long run, even harder to manage. Such autocratic alternatives provide no space in which popular resistance can be responded to and no forum through which differences in the ruling class can be contained. This, of course, does not stop segments of the ruling class, particularly finance capital, from periodically trying to push a dictatorial model.

The Organising and Disorganising Roles of the State System

What emerges from all this is a state system that broadly works, at the present moment, to maintain the unstable hegemony of the ruling class. Crucially, it also serves to organise the ruling class itself. Each of the institutions discussed above prevents internal contradictions within the ruling class from becoming too severe (to use our earlier example, they do not permit capitalists to routinely physically attack other capitalist competitors). They set the “rules of the game” in the form of laws, both for popular struggle and for the ruling class. They provide a forum for inter-factional struggle where each segment of the capitalist class, each fraction of ruling class opinion, can push its own interests and its own vision of what should be done. Finally, they ensure that whichever fraction wins gets to attempt its project, though it is of course undercut by both popular struggle and its rivals. All of this helps the exploiters to have some kind of meaningful unity, to think of themselves as a ruling class, and to define what the interests of that class as a whole are (i.e., what the so-called “national interest” is).

Meanwhile, the same process disorganises the working and producing classes. The constant message that is sought to be sent by this system is that collective struggle is meaningless and the only “useful” thing to do is to seek individual benefit. Thus, at every step, from the petty official to the Central government, the same pattern is followed in response to any resistance. Where possible, force is used to crush it. Where using that force would be risky – where it would expose the hand of the oppressor too much – some benefits are offered. These may be meaningful or meaningless (the larger the struggle, the more meaningful the benefits). The hope is that this offer will restore the original “balance of consciousness” by confirming that the state “takes care” of all. This will prevent people from realising their own power. The typical response of the neta to the constituent – “chinta mat karo main tumhara kaam karva dunga” (don’t worry, I’ll get your work done) – sums up the slogan of the bourgeois state. Meanwhile, every benefit that is offered itself becomes the subject of struggle, both by the resisting oppressed classes and by other sections of the ruling class and the state. Thus when the elected government may promise something, the bureaucrats will try to make it meaningless; where the bureaucracy collaborates the courts might step in; and so on. At every stage, the resistance is sought to be reduced to a “sectional interest”, while the government claims to represent “everyone.” All of this has the effect of frightening, bewildering, and ultimately exhausting those who are struggling.

A Common Analytical Mistake: Assuming that the Ruling Class Is All-Knowing and All-Powerful

There is a tendency by many, both among those involved in political struggle and among the general population, to see only half of this system and ignore the other half. The most common way this is put is to say: “The ruling class has anticipated what is going to happen and is undertaking such and such action in a diabolical ploy to confuse / divide the working people.”

Most of the time, such statements are half-true. They are true in that there is often a conscious effort to put in place policies. But such statements become untrue at two levels.

The first problem is that the “ruling class” does not have any one plan. There is no “invisible conspiracy” to run society – as should be clear from the history of any real society and from daily events. Certainly, sections of the exploiters, in small or big groups, are always conspiring, planning and trying to push their projects; but none of these sections represents the ruling class as a whole. Rather, they have to push these ideas through the state machinery, the media, etc. in an attempt to get them accepted both by the wider public and other sections of the ruling class. They have to convince, force or threaten everyone into accepting that their idea is the best for all. This is a battle for hegemony and it is fought both secretly and in public. Any victory is always temporary until a new attempt succeeds. In this sense, when such statements are made, the first response should be – who is pushing the said action, how, with what strength, and with what intentions?

Secondly, ideas and political plans do not solely originate from the ruling class. Indeed, new ideas only come from any section of the ruling class in response to a real or anticipated threat, either from their rivals or from the struggle of the oppressed. Thus every new idea and plan is marked by a two sided struggle, where one side is trying to disrupt the balance of power, and the other is trying to preserve it. In particular, when new politics arise among the oppressed, obviously different sections of the state machinery and the ruling class respond by attempting to dilute or confuse them. However, they can never do so completely. The final resulting idea is invariably a hybrid. Thus every idea contains contradictory tendencies. For instance, “development” can mean either state-driven grabbing of resources or provision of basic needs. “Democracy” can mean either elections with no real choice or genuine power to the people.

Indeed, the fundamental concepts of this system – “individualisation” of everything and the system protecting the “general interest” – also are contradictory. “Individualisation” can mean either alienating people from each other and destroying their mutual solidarity or it can mean respecting human dignity and freedom. The idea of a “general interest” for society is a lie in the present society because it is capitalist, not because there can never be a general interest.

These ideas did not originate from some conscious plan by a diabolical imagination. Rather, they are the current shape taken by the clash between ideas of a real, just and free society, on the one hand, and the reality of a capitalist system that does not permit such a society to exist. In the process most exploiters themselves believe in these concepts because to do otherwise would be to admit that they are both evil and doomed. The key to expanding the revolution is to look for these contradictions in ideas.

The fundamental problem with looking at social change as the result of some “master plan” is that it blinds us to the real power of the working class and forces us to accept the myth that the capitalists are rational, organised and planned. This becomes particularly dangerous when it leads to the assumption that just “taking over” the capitalist state will allow one to bring justice to society. As we noted above, there is no single “state”, the various components of the state are themselves areas of conflict, and merely seizing one part – such as control of the formal government – will not stop the class struggle. The structure of power in a capitalist society has to be challenged at every level for true socialism.

A Way Forward

What does this mean for the political struggle? In a very brief summary, the following points can be noted:

The goal is not a single revolutionary movement headed by a single party. Nor is it for a takeover of one or the other centre of power – the elected government, the army, etc. Rather, it is for the hegemony of the capitalist ruling class to be replaced with the hegemony of the workers and the producers. This is a battle against their fundamental structures of power, which is also, and always, a struggle over ideas. The more that struggles can counter the fear, dependence and mental confusion created by the existing system, the more that it will be weakened, and the more that the majority will attain both the power and the clarity to bring socialism into existence.

(Image courtesy - worldpublicunion.org)

- New Path