The dictionary gives the following meaning for the word history: ‘Knowledge accumulated through research, past events, memories, collections, groups, gifts, information about events’. Let us take the meaning as ‘the path that was crossed’. There is a saying ‘those who don’t know the way they came won’t understand the way they are going’. It is not only to shed tears at past sacrifices and feel pride in talking about what happened that we recall the past. We also do it to ensure that the valor and sacrifices of the past show the way forward for the next generation.

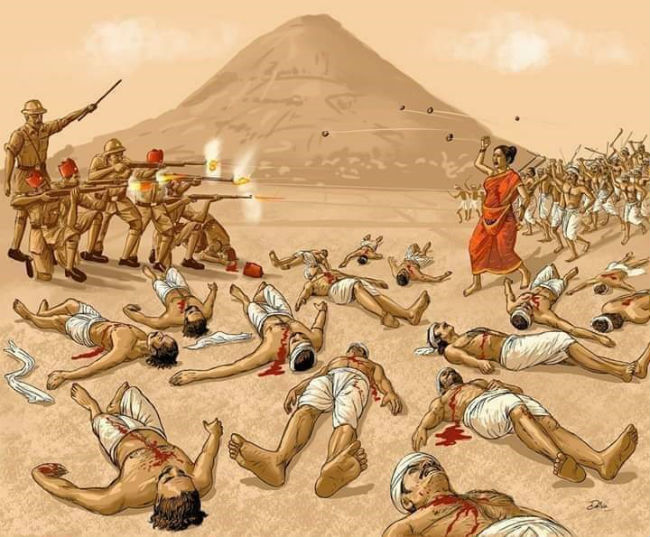

On April 3, 1920, a huge mass protest took place against the oppressive British laws in the village Perungamanallur, near Usilampatti, Tamilnadu. 17 people, including a woman ‘Mayakkal’, were shot dead in the gunfire perpetrated by the British government to stifle the protest. With this year, it’s been a hundred years since this painful event in the Tamil people’s struggle against imperialism occurred.

We have seen historical narratives of common people fighting for justice in literature. This horrific incident in Perungamanallur of Madurai district, which is called the ‘Jallianwala Bagh of the South’ is an important part of the history of such people in the last century. A history of sacrifice, of 17 people dying of bullet wounds for their rights!

We have seen historical narratives of common people fighting for justice in literature. This horrific incident in Perungamanallur of Madurai district, which is called the ‘Jallianwala Bagh of the South’ is an important part of the history of such people in the last century. A history of sacrifice, of 17 people dying of bullet wounds for their rights!

This protest happened against the Criminal Tribes Act, one of the most horrific laws to be enacted in the history of the world. Identifying a person as a criminal on the basis and birth and a specific group as horrific, and continuously monitoring their actions was a consequence of the European influence.

Historians note that nomadic communities played an essential role in the French revolution. During the period of the revolution, France faced a severe economic crisis; food prices shot up as the crop yield continued to be low; workers were thrown out of their industrial jobs with this as the justification to do so; they roamed throughout the country searching for jobs; the village folk migrated towards cities; notably, thousands of people migrated to Paris.

A majority of the agitations that took place towards a revolution in years like 1778, 1784 and 1789 were a consequence of this widespread inflation. It is notable that these protests forced into effect the reduction in prices of food and food items. At the same time, protests flared up in Paris as well. During this period, along with the breakdown of law and order, France also came under the throes of an economic crisis. The number of homeless people increased; unemployment and inflation pushed the majority of common people to a state where they depended on begging and stealing to procure food.

When people took to the streets to protest against this state of affairs, the ruling classes unleashed repression on them. When people tried to fight back against this, they were branded as violent and dangerous groups. People who were already struggling to survive, like beggars, the homeless and nomadic communities were declared to be brutal and their names recorded by the state. Identifying their nature and numbers, the state continued to keep their actions under surveillance.

In 1824, an oppressive law called the ‘vagrancy system’ was brought into effect in order to control and monitor those who were involved in protests happening in many European countries including England and France, people like nomads and the homeless. Through this, to ensure that people don’t raise up against state authority and the ownership of private property by a very few in society, they were categorized as dangerous groups and subject to repression.

Moreover, at the beginning of the 19th century, a system was coming into place wherein criminals were categorized by their body structure. It was thought that people with features like a small head, one eye, large eyebrows, a flat nose, a rigid jaw and large ears were predominantly predisposed to ‘criminal intentions’ psychologically. Because one’s bodily structure is based on birth, there was a subtle inference formed that criminal thoughts also originate on the basis of birth.

Present-day scientists have proven that there is no connection between a person’s bodily structure and their criminal acts and that the idea is not backed by any scientific proof. But it was on the basis of such scientifically unproven European ideas that the British colonial rule introduced the concept of ‘criminal tribes’ in India.

When the British first entered, what is today known as India, this vast landmass was being ruled by various big and small kingdoms alike. The British established their colonial domination by conquering these lands through fighting or tricking these different kingdoms and consolidating them. Many independent ethnic groups were living in the lands that were conquered to establish British rule during this period. They were mostly not under the control of the current kingdoms but sovereign groups that administered themselves through self-government.

The British were not able to bring these free ethnic groups entirely under their control. When the British tried to control them, these groups responded with violent resistance. Even when the British succeeded in repressing them through their military might, they were unable to bring these groups permanently under their administrative laws. They thought that some brutal laws would be required to achieve this. The ultimate form of that is the Criminal Tribes Act. Nomadic groups, some mountain-based ethnic groups, and some other caste groups based in the plains were brought under this Act.

The British were also confused about monitoring, with India being a mixture of many different regional languages. From the 17th century, nomadic peoples lived away from the majority in forest areas, with the British colonial government’s modern economic and political ideologies leading to deep economic exploitation. Their culture and heritage were different from those of the general population. Some members of these groups were also involved in thievery due to poverty. Instead of abolishing thievery, the British government declared the whole of such ethnic groups as criminals and started torturing them.

People of Dakki ethnicity from the areas surrounding the Bengal religion were the first to be adversely impacted by this brutal law that declares whole groups as criminals and tortures them. Thousands of Dakki people were hunted through human trafficking, life imprisonment and murder by hanging. This bloody hunt was perpetrated, particularly between 1835 and 1850. Thinking that these mechanisms could also be used to repress protests against the government, the British government decided to conduct this sort of hunt all over the country.

The British government enacted the Indian Police Act in 1861. According to this, a police system modelled on the European one was created throughout British India. This outlawed the already existing traditional policing systems. This is how members of castes like Kallar, Maravar and Valaiyar who worked as direction and temple sentinels in southern Tamil Nadu according to the traditional system lost their occupations. The lands that were set aside for them as security subsidies were confiscated and the wages they were being paid for their work until then were also made illegal. They were pushed into poverty because of this. Protests erupted. The British used these protests itself as a reason and identified even these people as criminal tribes.

The British colonial government’s modern economy and political ideologies brought about sweeping changes in Indian society. Notably, the traditional occupations of many ancient communities were abolished. Due to this some nomadic groups that used to work as travelling salesmen started losing their daily income. Moreover, they were enemies to the British ideology of modernizing markets. They went from town to town, going directly to people’s residences and selling their products through the barter system. This was against the modern market system where products are gathered together in one place and sold there. Therefore it became necessary for the British to control these nomadic merchants and restrict them to one place. Because of this, nomadic merchants clashed with market traders in many places.

Enraged at their traditional occupation being crushed, these nomadic merchants started confiscating the vegetables, products and stores of the market traders. It was only because of this that they were identified as a thieving community. Particularly, ethnic groups like Banjaras, Lambadis and Kuravars were traditionally involved in salt trade along with some kinds of grains which they traded by travelling from town to town using cattle. In the 1880s the British government took over salt manufacturing. Moreover, it decided to establish a monopoly over salt manufacturing. Due to this, these travelling traders were pushed to a situation where they were forced to buy salt from the government. Enraged at seeing the government transporting the products which they had been taking around on cattle for a long time in trains, they employed counter- measures. They were identified as train robbers showing this as the reason to do so.

It was around the above situations that the Criminal Tribes Act was enacted in India. At the end, the effort taken to control groups in North India who were occupied in preparing fake coins was what gained the form of the Criminal Tribes Act. First, some laws were created, which allowed arrests without a warrant and made it impossible to get bail. Finally, in 1871, all these laws were consolidated into the Criminal Tribes Act that categorized ethnic groups which were considered to be involved in criminal activities, continuously monitored their actions and restricted their movements to one place.

The Criminal Tribes Act was first brought into effect in the North Indian regions of the United Provinces, Punjab, the North-West Frontier regions and Bengal in 1871. The Act was revised in 1896 as there were practical difficulties in extending it to other regions. The laws that were revised in 1896 were further streamlined and brought into effect in 1911.

In between, the British colonial government introduced a new Forest Act in 1878. Hunting activities practised by the mountain-based ethnic group who had until then lived considering these forests themselves as their property was made completely illegal. But, to take care of their livelihood requirements, they continued to hunt and trade the rare products they gathered in the forests. This became the reason to say that these people were continuously engaged in illegal acts, and they were also declared to be criminal tribes. In this way, mountain-based tribes, including the ‘Yenadis’ were considered to be criminal tribes.

After the Criminal Tribes Act was brought into effect in 1911 following revisions, they declared an additional few castes and indigenous communities as criminal tribes and started registering them. By this, throughout the Madras province, 14 lakh people were brought under this law.

If we go into the specifics, the British government used this Act against everyone they were scared of and everyone that raised voices against them. Step by step, this Act was extended to the whole of India. The British government added approximately 213 castes to the criminal tribes list. Even when the Criminal Tribes Act enacted in 1911 was extended to the Madras province, the final guidelines to bring it into effect were only released in May 1913. Eighty-nine castes in Tamil Nadu were included in this list.

List of those who were declared as criminal tribes by state and district

First, let’s see those who were declared as criminal tribes in the Telugu districts of Chennai Rajdhani.

In the Ganjam district, the indigenous communities of Thelusu and Bamulas in 1917 and the indigenous community of Yundhasis in 1923 were declared as criminal tribes.

In the district of Visakhapatnam, in 1914 the caste of Konda Baatus, in 1915 the indigenous community of Rosis, in 1916 the indigenous community of Kindali and in 1921 the indigenous community of Chalungas were declared as criminal tribes.

In the Godavari district, in 1913 the Denga Dhasaris, in 1915 the Nakkalars and in 1925 the Anippal Malas, in the Egenji district and in 1926 the Oriya Dombars were declared as criminal tribes.

In the Krishna district, in 1913 the Donga Erakkulas and Donga Ottars were brought under this.

In the Guntur district, in 1923 the Jagir Palli Maadiyas, in the Nellore district in 1913 the Domaras, the Boyars in Kurnool district in 1918 and the Sukaalis were brought under this Act.

In the Bellary district, in 1913 the Donga Erakkulas and in 1923 the Donga Dhasaris were brought under this.

In the Anantpur district, in 1923 the DongaOor Kuravars were brought under this.

In the Kadappa district, in 1923 the Thogai Malai Kuravars and Capemaris were brought under this.

In the Chittoor district, in 1923 the Yenadis and Irulars were brought under this.

Now, let’s see which castes/ethnic groups in Tamil Nadu were declared as criminal tribes.

In the North Arcot district, in 1913 the Thogai Malai Kuravars and Salem Melnadu Kuravars, in 1914 the Vaaganur Paraiyars and Jogis, in 1916 the Chakkarapalli Kuravars and in 1922 the Thottiya Nayakkars were brought under this.

In the Chengalpet district, in 1913 the Veppur Paraiyars, in 1914 the Jogis and in 1923 the Kal Ottars were declared as criminal tribes.

In the South Arcot district, in 1913 the Aathur Kizhnadu Kuravars and in 1914 the Vellikuppam Padaiyatchi were brought under this Act.

In the Salem district, in 1923 the Uppu Kuravars, in 1924 the Chakkaravalli Kuravars and Monda Kuravars and in 1934 the Suramarai Ottars were brought under this.

In the Coimbatore district, in 1918 the Valaiyars and in 1922 the Thottiya Nayakkars were brought under this.

The Kauravars living within Madras town were brought under this in 1924.

In the Trichy and Thanjavur districts, in 1913 the Gandharvakottai Kuravars, in 1915 the Koothappal Kallars, in 1917 the Ooralli Gounders, in 1923 the Periya Suriyar Kallars and in 1924 the Vettuva Gounders were brought under this.

In the Madurai district, in 1928 the Piramalai Kallars, in 1915 the Chettinad Valaiyars, in 1923 the other Valaiyars and in 1922 the Thottiya Nayakkars were brought under this Act.

In Ramanathapuram district, in 1915 the Uppu Kuravars, in 1916 the Vaduvarpatti Kuravars and Karumbavars, in 1923 the Sembanattu Maravars, in 1932 the Kaaladi Pallars, in 1933 the Aapanadu Kondaiyan Kottai Maravars and in 1934 the Kal Ottars were brought under this.

In the Tirunelveli district, in 1919 the Poolam Maravars and in 1932 the Koyilpatti Uppu Kuravars were brought under this.

According to this law, the District Collector could declare any caste as a criminal tribe; the court could not question that; there was no differentiation between criminal and innocent; that law said that all people born in one caste were criminals by birth. Members of castes under the list who were above the age of 16 had to register their name, address and fingerprints in the police station. Men were prohibited from sleeping in their houses during the night. They had to sleep under police surveillance in the police station or other common sheds. There was no exception from this rule even for old and newly married men.

Even if they had to go out of their house and travel to other towns between sunrise and sunset, they had to possess a Raadhari slip (permission slips provided by village heads). They were liable to imprisonment for a period from 6 months up till three years if they transgressed these rules. They could be arrested even by the Thalaiyari (?) if they crossed the imposed border. Even if somebody’s behaviour was suspicious, they were liable to 3 years of imprisonment. A case was registered against this Act because they were found with a matchbox and a pair of scissors in their hand. Many oppressive sections like this were present in the Act.

This Act induced uncontrolled police oppression. Officials in two places had to be paid bribes in order to procure the Raadhari slip. That they were only able to manage the cost of bribes by selling a chicken tells us the extent of oppression. Due to these oppressive measures, farming work was disrupted, poverty increased, people had to run from pillar to post because of false cases, losing whatever meagre land they had held before.

The Madras Police headquarters ordered the district police in 1914 to prepare and send a list of all those to be added under the Criminal Tribes Act in Tamil Nadu. The British Police introduced this law for the first time in Tamil Nadu in the Keezhakuyilkudi part of Madurai on 4.5.1914.

The civil judge of Madurai district began the process of registering the Kallars under that list. As the first step, 70 out of 320 men were punished under the law. Accepting the judge’s recommendation, they were notified as criminal tribes and kept under police surveillance. Because of this, every person above the age of 16 had to register themselves. Those who had registered themselves in this manner had to notify the government of details regarding their place of residence and outside travel according to section 10 of the Criminal Tribes Act.

The process of registering people according to the Criminal Tribes Act was started in the Thirumangalam taluka of Madurai. Kaalapatti, Pothampatti, Perungamanallur, Thummakundu and Kumaranpatti were the towns selected in the first phase. Even though the registration process was happening at a fast pace, it wasn’t that easy.

Railey, who was the district civil judge then, had allotted a deadline of 1st January 1920 for the registration process to be completed. But registration had been completed only in 11 of the 158 selected villages by that date.

When the Kallar population was approximately 60000, only 3000 among them were registered. Moreover, the authorities were angry after finding out that only a thousand people had come to get themselves registered. The district police monitor continued to maintain that it was essential to register the Kallars in large numbers. Not stopping at that he also ordered that everyone who was registered as part of a criminal tribe had to report to an external police station that was at a 5-mile distance from their residences within 11 am and 4 pm.

Resistance arose among even innocent people against the government’s Criminal Tribes Act. All over the country, the members of declared criminal tribes began engaging in resistance activities. At the same time, the police were not able to pin crimes on members of the same community who were wealthy and had possessed influence. When the authorities were quickly executing this law in the parts of Madurai highly populated by Piramalai Kallars, they came to the village of Perungamanallur as the last phase. The people of this village refused to submit to this law. They firmly announced that they would only obey laws that were true and just and they wouldn’t submit to laws that were against social justice. The Madurai District Collector was firm that the law should be brought into effect there no matter what.

Thinking that people would engage in agitations against the government, the British government sent cavalry and armed forces to keep the place under control. Even when the people said that a law which doesn’t differentiate between criminals and innocents and considers the whole community as criminals was wrong, the British government refused to listen to their concerns. The people argued many times with the government over this.

Days were also passing. The authorities came to a decision. On 2 March 1920, the police started setting up camps along with the fingerprint registration authorities near the villages. Before they entered the villages, the elders and influential people in these communities accosted them and said 'this is a great injustice. Kallars are farmers, not brutal creatures. Therefore, we won't accept it if you come to our village and take our fingerprints', thus registering their protest. They also said that 'we'll go to Madurai and talk with the collector'. Following this, the authorities postponed their activities. After this, the elderly members there went to see the collector in Madurai and submitted a petition.

In between all this, the Madurai district civil judge issued an order on 29 March 1920 asking members of the Kallar caste above the age of 7 residing in Perungamanallur to report before the independent sub-collector at 11 am on April 2 & 3, 1920 for registering their fingerprints.

In this situation, members of that community from Perungamanallur and other villages gathered at the temple on 1 April 1920. 'The British Government is trying to make us submit by using weapons. Portraying innocent people as criminals and asking us to register our fingerprints at the police station is a great humiliation. Our honour is more important than even our life. We will revolt against this together without submitting to the government's wishes', they decided.

Police set up camps near the village of Perungamanallur. Seeing the police advancing, the people engaged in protest by raising voices for their rights. 'We won't allow the police inside the village; go out!', they cried. At that time, a discussion happened between the village leaders, police and income tax authorities. When the discussion proved to be useless, people were further enraged. Without lending an ear to the protest, police forces advanced towards the people. The sub-collector suggested to the civil rights judge that he order the police to shoot at the people in order to repress their war cry. Upon his suggestion, the order was issued. Hearing gun sounds, a few young people rushed to confront the British police forces.

The guns of the British took away the lives of 17 people. The bodies of these 17 people who had attained a brave death were gathered in a bullock cart and buried in one huge pit on the riverbed near Usilampatti. The police attacked a brave woman named 'Mayakkal' for helping those who were revolting during the police shooting by bringing them water, by stabbing her with the knife of the gun and killed her. Caught in this brutal shootout, people scattered away in fear; approximately 200 of these people were caught and shackled with a long chain that bound together both hands with one leg and taken to the Thirumangalam court that was located at a 20 km distance by foot like cows and goats, and remanded there by the authorities.

Protest against the Perungamanallur massacre

Lawyer George Joseph fought the case of these imprisoned people in the remand court. Due to his contribution, these protestors were freed. He was of service to these protestors by fighting their case without accepting any kind of remuneration for his work.

Lawyer George Joseph was a Malayali. He was a practising lawyer living in Madurai. He was the one who for the first time, was helping these people confront the Criminal Tribes Act legally. His efforts in this regard started from 1915 onwards.

After the Perungamanallur police shoot, he gathered together more than 200 village folk and first staged a massive people's protest in Madurai. He also protested asking that the police should not investigate the Perungamanallur massacre and that an independent investigation team should be formed under the leadership of a judge. Because of the love these people had for lawyer George Joseph, he was addressed as 'Rosappoo Thurai' by the Kallars in that area. A tradition persists to this day by which children are named 'Rosappoo' in his memory.

The shootout that was conducted on the innocent people of Perungamanallur echoed in the British Parliament. The parliament urged that it was unacceptable that the police had shot illiterate poor innocent farmers and advised that funds should be set aside for the educational, economic and social development of the people in that region, along with the provision of relief measures. The British Government in India acted to set up a separate department devoted to the social reform of the Kallars and took efforts to introduce many beneficial schemes.

People’s movement against the Criminal Tribes Act

Mr. Gopalasamy Regunatha Raajaliyar had met King George V in person in 1911 itself regarding the removal of Kallars in the Trichy and Thanjavur districts from the list of criminal tribes and thereby recovering the Thanjavur district Eesanattu Kallars from the list of criminal tribes.

Likewise, the Seyyur Adi Dravidar Conference and the Vanniyarkula Kshatriya Sabha fought hard and removed their respective castes from the list.

After lawyer Joseph, ideologically left-leaning friends continuously undertook campaigns against the Act. On the basis of their resistance to imperialism, they fought to end this horror.

Mr. Muthuramalinga Thevar spoke to Comrade Jeevanandham in Madurai about the need for a massive people's protest against the horrors that continued to be perpetrated even after so much resistance and joined forces with him for campaigning. Following this, Muthuramalinga Thevar along with Comrade Jeeva and Comrade Ramamurthy and Janaki Ammal from the Communist Party, gathered together people and conducted continuous campaigns and protests against the Criminal Tribes Act. Elderly communist leader Comrade Th. Pandian has recorded that Comrade Jeeva told him that the three of them conducted campaigns in the villages near Usilampatti, in his book titled 'Jeeva and Me' (title translated). Because of these campaigns, people belonging to these communities gathered together in huge numbers to raise their voices. The reason for their response was the government's brutal repression and the consequent dire poverty.

'Mr. Muthuramalinga Thevar, Comrade Jeeva and Comrade Ramamurthy travelled from town to town conducting campaigns in order to gather together members of the Piramalai Kallar community from Sekkanoorani up till Koodalur against the Criminal Tribes Act. Because car journeys were rare in those times, they travelled in bullock carts, horse carts and by foot in roadless areas to conduct these campaigns.

When they went to conduct these campaigns, people in the grip of poverty expressed their love by making them sit on rope cots and offering them buttermilk and porridge along with onions and dried fish to bite on', this he records in the book. In the section on the Criminal Tribes event, "The British government used people from other castes to control the Kallar people who were declared criminals. This was the reason for the growth in a conflict between Piramalai Kallars and other castes. Sometimes, they would make an inferior youth climb on the back of an important person in town and make him carry the young man in the name of punishing mistakes. If the young man refused to climb, he would be beaten. No one could say what would happen the next day if he climbed…"

In such ways, the police force which worked for the British sowed the seeds of conflict between different communities and sharpened them. Comrade Th. Pandian mentions in his note that the reason these issues continue to exist even today is that the police still follow these kinds of practices today.

Comrade Jeeva records very important information about the damage this Act inflicts "..We were able to gather even Christian priests against this Act. Moreover, we put together a caste wise list of those imprisoned under the 'Criminal Tribes Act' in the Madurai, Palayankottai and Coimbatore jails. We realized that people belonging to all castes were imprisoned against this Act. (Among those numbers) the number of people belonging to the Kallar caste was low. Mostly, they were only cases of stealing cows and goats" he says.

When we look deeper into this information, we will be able to realize that these laws were used by the British government to repress the farming communities who were mostly behind the Palayakkarars revolt that took place in the landmass in between the Madurai – Trichy – Thanjavur - Coimbatore region and to divide and rule them.

Congress promised that they would repeal these laws in their 1937 election campaign. Believe this promise of the Congress, Muthuramalinga Thevar even conducted campaigns in support of the party. But even after many months had passed since they came to power, Rajaji didn't come forward to repeal this Act. Therefore, he protested against this and was arrested. Mr. Muthuramalinga Thevar became the first Congress leader to be arrested during Congress rule. Comrade Jeeva and Comrade Ramamurthy continuously protested demanding his release. The Brahmin rule that on the one side imposed 'Hindi' and refused the rights of the Tamil people, on the other side refused to repeal the oppressive laws of the British government. The Brahmin government that imprisoned Tamil scholars who opposed Hindi also continued to implement laws that destroyed the lives of the Kudiyanavars. After this betrayal of the Congress, the leadership of the resistance movement against the Criminal Tribes Act lost belief in the Congress and opted out.

The Criminal Tribes Act and resistance at the Indian level

When on one side, the people's protest was coordinated on the field, on the other resistance to this Act also started growing at the national level. In 1933, Dr. Ambedkar the horrific nature of this law and methods to arrive at a solution for the same in an investigation conducted before the Indian Constitutional Reform Committee."I urge you to think of the terrible situation that those belonging to the so-called criminal tribes find themselves in. Members of these criminal tribes are scattered among this country's population. I'm talking from the experience I had in Bombay. That law provides some powers to the Governor to discipline the movement of these people and safeguard their wellbeing. Under chapter 108 of the Act, the Governor can issue certain orders. Can't measures be taken to safeguard the wellbeing of these people who are scattered throughout the country and raise their standard of living? When they come to know that someone is from an indigenous community, can't the Governor enact some laws for their benefit? What does it matter if they're in an excluded region? Or if they live among the general population? This law that was enacted by the British has been nothing but disadvantageous for the specified ethnic communities wherever they may be", thus he spoke.

It was during that investigation that Dr Ambedkar pushed the Indian government to record that the respective state governments had more authority than the Governor appointed by the Indian government to amend the Criminal Tribes Act, to provide rehabilitation for those who were added to the list of criminal tribes, and to control these communities.

People's protests were coordinated against this Act. Efforts were also taken to gather people who were not affected by the Act for these protests. They assembled farmers from Vadugapatti along with Maravars under the Criminal Tribes resistance group. During that time, members of the Aapanadu Maravar community assembled under the leadership of Mr. Muthuramalinga Thevar against this Act. That was when the 'Criminal Tribes Act resistance committee' was formed. That committee called for a conference under the leadership of popular Congress leader Mr. Varadarajulu Naidu on May 12, 1934, at the town of Abiramam situated near Kamudhi. He was the one who had struggled alongside Periyar in the Cheranmadevi Gurukul revolt.

It was only six months before this conference that Periyar had been arrested in a treason case and lodged in the Raja Mahendram jail under rigorous imprisonment for writing an essay titled 'Why should today's governance system be abolished (?)'. Mr. Varadarajulu Naidu met him in person. It is only after that he comes to the Criminal Tribes Act resistance conference.

It was there that a resolution was passed demanding the complete repeal of the Criminal Tribes Act. Many people belonging to various caste groups that were not directly affected by the Act also assembled for the conference. Following this conference, the Piramalai Kallars also participated in the protest.

At that time, all the socialist thinkers who were part of the Congress government got together and formed a group called the Congress Socialist Party. Abolition of the Criminal Tribes Act was added to the political agenda of the Congress Socialist Party. A huge resistance group assembled under this leadership for the abolition of the Criminal Tribes Act. As part of this, Mr. Muthuramalinga Thevar, Comrades Jeevanandham, Ramamurthy, Janaki Ammal, Sasivarnathevar, R.V Swaminathan, Dinakar Sami Thevar, along with people like the popular theatre artiste Viswanathadas travelled from village to village conducting campaigns. After a huge crowd gathered listening to the songs of Janaki Ammal, the other leaders began their speeches and brought out the fervour in people.

Repeal of the Criminal Tribes Act

In 1919, the British government met with different sections of people to learn their opinions in order to provide power to the people living in the Indian Union step by step. T.M Nayar, K.V Reddy and Sir A. Ramasamy Mudhaliar put forward their opinions on behalf of the Justice Party and Dravidar Sangam. On that occasion, T.M Nayar asked for the formation of a Maravar Mahajana Sabha, thereby going on record about those people's problems and concerns as well.

The Justice Party which came to power after the Perungamanallur protest made some amendments to the Criminal Tribes Act and rescued a majority of the Kallars from the throes of the Act. An I.C.S Commissioner was appointed specifically to oversee the reform of the Kallars under the designation 'Labour Commissioner'. On the basis of his recommendations, the Justice Party implemented the 'Kallar Reform Scheme' with full force.

- Bank loans were provided for the Kallars to start their own permanent businesses.

- Free residential quarters were built for the Kallars which were also managed by the government authorities.

- Vocational training was provided to youth who were then set up in various parts of the province.

- More than 100 schools were built for the Kallars in Madurai, Dindukkal, Usilampatti, Chinnaalapati, Sempatti, Thirumangalam and Theni.

- The Justice Party government assumed the responsibility of Kallar schools that were neglected by the Kallar Mahajana Sangam in the Thanjavur district.

- Free lands were provided for the Kallars to undertake farming.

- Kallar country regions were also connected to the Periyar Dam Irrigation Project, enabling the Kallars to engage in farming in the Theni, Dindukkal, Madurai and Ramanathapuram districts.

- In 1922, in a situation where the Kallars were unable to repay the loans they had received for farming from the agricultural cooperative societies, the Central Bank that had lent funds to these societies began to apply extreme pressure on them. The provincial government itself gave funds to the 34 Kallar cooperative societies that were helpless, thereby solving the problem; the government also provided loans for the next phase of farming.

Like this, many beneficial schemes that supported these people were provided for in the Justice Party rule.

Even when there was an opportunity to amend the black law of the British government, no efforts were taken towards this during the Brahmin dominated Rajaji rule. Rather we saw that oppression and repression were unleashed all over Tamil Nadu. In a manner so as to not hurt the sentiments of the British, the Rajaji government did not come forward to make any effort in opposition to this Criminal Tribes Act. The Brahmin leadership of the Congress also did not take forward the resistance to this Act at the national level.

It was those who were representatives of the common people that rose against the brutal repression which British imperialism brought upon common folk, on the field, in legal struggles and in the people's assembly that is the legislature. These protests will make it clear to us that the high caste crowd did not show any concern towards the people oppressed by the Criminal Tribes Act, rather choosing to join hands with imperialism.

The resistance movement to this law that became more intense due to the early efforts of Mr. Muthuramalinga Thevar and those friends that engaged alongside him in fieldwork offered a solution after the transfer of power in 1947. Finally, when India's freedom, i.e. transfer of power was confirmed, a draft law was brought forward for the complete repeal of the Criminal Tribes Act in the Madras Legislative Council on 17 April 1947. Minister P. Subburayan, one of the leaders of the self- respect movement, gave a speech proposing the same. Congress MLA Paganeri R.V. Swaminathan spoke in detail about the horrific nature of the Criminal Tribes Act and why it should be abolished.

Very few people spoke in support of the Criminal Tribes Act. After heated debates in the legislature, a resolution completely abolishing the Criminal Tribes Act was finally passed with majority backing. It was sent for the Governor's approval on 30 May 1947. A government order for the abolition of the Criminal Tribes Act was issued on June 5.

The horrific incident that took place in Perungamanallur 100 years ago was against British colonial governance systems. Not only that, but we should also see it as the Tamil people's resistance to imperialism and a protest that was based on the rights of the Tamil people. Tamil nationalism is based on the united protest of people subject to oppression. It is not based on the conflicts between them. In that way, Perungamanallur stands in history as a symbol of Tamil nationalism. That both in Kilvenmani and Perungamanallur, the two great sacrifices/protests and in the ensuing journey for justice, the whole Tamil community stood together instead of only a particular caste group protesting, stands testament to this fact.

Teach the histories related to these protests to your children and the next generation. Rather than putting up a 3000 crore statue for the Brahmin- Hindutva leaders of the Congress who didn't write, speak or protest against the Criminal Tribes Act, the government should build memorials for the Tamils who died protesting the British and fulfil the demands of the next generation of those affected.

Today, in those same Western Ghats, hugely destructive projects that are against the Tamils like Neutrino in Thevaram and the nuclear waste facility in Vadapazhanji are being proposed, a project that submit blatantly to imperialism. It is very timely to recall the brave history of the Perungamanallur people who stood courageously against imperialism in this situation. Let us pay our brave respects to those valorous people who resisted imperialism.

Written by May 17 Movement

Translated by Alagammai

You can send your articles to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.